Is there a correlation between happiness & income? A large smartphone study challenges old insights

"When I was young, I thought that money was the most important thing in life; now that I am old, I know that it is." — Oscar Wilde

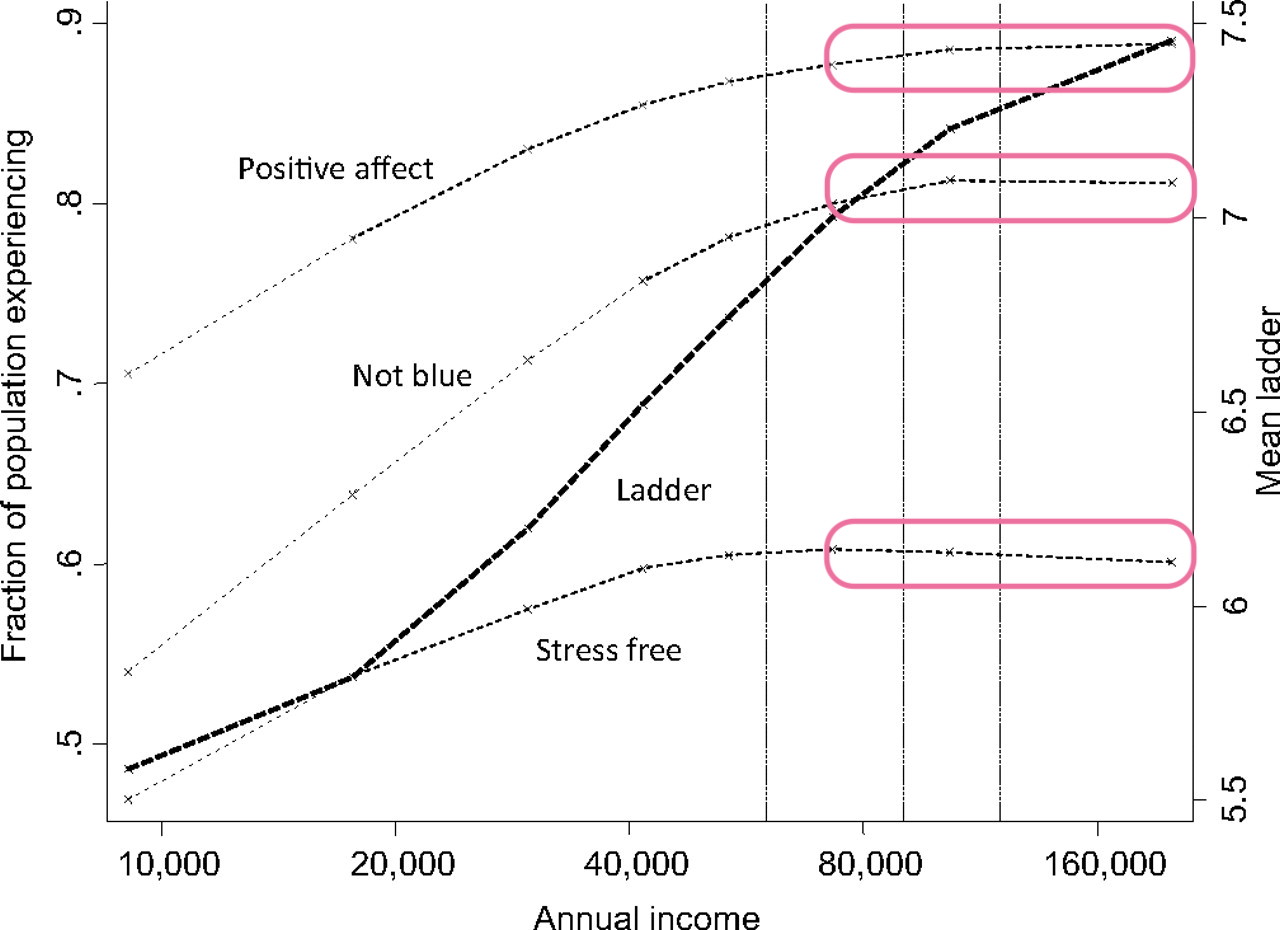

Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton explored this question in their well-known 2010 study High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being, which even garnered mainstream media attention. They distinguished happiness into two separate psychological concepts — emotional well-being and life evaluation. Emotional well-being represents one’s daily mood, measured by asking individuals if they experienced a certain type of emotion the day before (happiness, stress, enjoyment, etc.); life evaluation refers to individuals’ thoughts about their life in general, measured on a scale of 0 to 10. After analyzing the responses of about 1,000 participants, results showed that while higher income always correlates with higher life evaluation, emotional well-being stops increasing and plateaus once annual income reaches $75,000 (€61,854).

Fig 1 Three factors of emotional well-being plateau over $75,000 annual income

Large smartphone-based study from 2020 disputes well-being plateau#

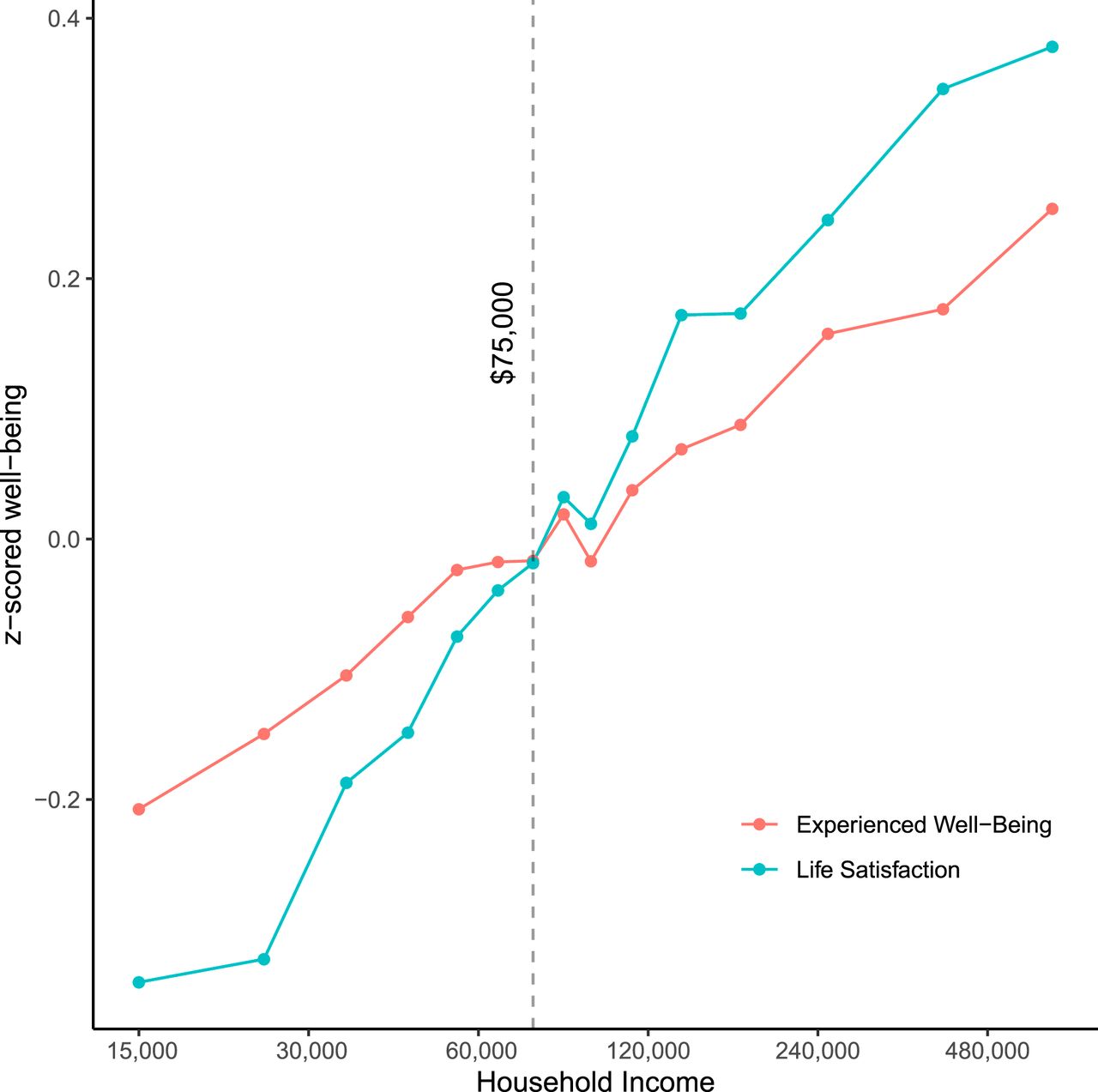

Matthew Killingsworth challenges this claim in his aptly-named 2020 study Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year , based on reports on the relationship between money and well-being from 33,391 participants. The results show no evidence of a well-being plateau above $75,000/year, meaning that higher income linearly increased for both, daily emotional well-being and life satisfaction. This begs the question: What changed from 2010 to 2020?

Fig 2 Mean levels of well-being (real-time feeling) and evaluative life satisfaction by income

To investigate experienced well-being, the 2010 study used a traditional survey. It required participants to give an estimated feeling based on their daily memories, which is prone to memory errors and cognitive biases. To measure people’s emotional well-being directly, instead of their “remembered well-being”, Killingsworth used smartphones to collect spontaneous, real-time data to reduce hindsight bias. The questionnaires were triggered at random times without deliberation time. Killingsworth also extended the binary response format of Kahneman and Deaton to a continuous response scale that allowed for finer distinctions between different intensities of emotion. The binary format had the effect that 70% of people with the lowest level of income already registered at the highest level of positive feelings. The plateau they identified was in fact a ceiling — of their methodology and data!

How researchers can benefit from smartphone technology#

Researchers who study human behavior can benefit from collecting data using smartphone sensing. In this particular case, Killingsworth could, for example

-

validate his real-time questions with location data, to ensure participants are only questioned at their home;

-

use app sequences to infer whether participants sleep enough, and

-

measure social media activity, to gauge participants happiness.

As this example shows, new methods and technologies help correcting old research errors and generate new results from a strong, unbiased data foundation. If you have a research idea or data to validate and would like to know more about new research methods with smartphones, get in touch.

About the author

Clara Vetter

Related Posts

Most used smartphone apps of 2020 – Whatsapp, Instagram and Facebook at the top

Objective alternatives to surveys in empirical research